Michel Foucault, Histoire de la folie à l’âge Classique. Entretien avec Michel Foucault. Diffusion le 11 juillet 1961 sur France III National. In Entretiens radiophoniques, 1961-1983, Flammarion / VRIN / INA, 2024, pp. 17-19.

[…] no other society except ours, grants the status of mental illness alone to the madman. In all other societies, the status of the mad is much more complex and in a sense richer. The mad have a religious significance, a magical significance. The madman is out in the open, his manifestations eagerly awaited with attempts made to decypher them. But this kind of annihilation by psychology, medicine and mental pathology is characteristic of our culture; and up to a certain point at least, it’s an impoverishment. (p.19) [1]

One of the engaging features of Foucault’s work is the myriad of different angles from which he approaches his various ideas, and his ongoing subtle, and sometimes not so subtle revisions subsequent to his first formulation of an idea. This creates complex layers of meaning from different perspectives, rather like viewing a faceted precious stone from different angles and in different lights. In this context, and in the general context of these early interviews by Foucault, I would like to draw attention to work done by librarians at the Henri Piéron library in Paris on annotated copies by Foucault of his principal doctoral thesis on the history of madness and complementary thesis on Kant (Le Doeuff & Lesage, 2025). Even in these early annotations, we can see Foucault’s characteristic shifts in thinking, his introduction of new nuances and angles. There is never a fixed end point in his writing; it is always exploratory and experimental rather than didactic. As he once said, he always thought and hoped the book he had just written would be his last, but then he found that it raised even further problems – both for himself and others – which he felt obliged to address.

In the second interview in the Entretiens Radiophoniques we see a continuation of this process, adding to the general difficulty and complexity of interpreting Foucault’s position on any given concept. In combination with Foucault’s often poetic and literary style, this can produce effects that are either exciting or baffling for readers. Frédéric Gros, who has edited and written extensively about Foucault’s work, comments on this, explaining he was ready to abandon the idea of an academic career before reading the History of Madness, but found Foucault’s work so intriguing that he decided it was worth it after all:

‘I didn’t understand a word, but I was captivated by the gritty texture of the text. I was impressed, seduced and carried away by the movement of the writing. There was something like a kind of lyrical inspiration there. I couldn’t get my bearings and had trouble distinguishing what was important from what was incidental in the text. It was a real experience of strangeness’ (Gros, 2025).

Others, however, have found this effect highly irritating– notably a number of Foucault’s early English language critics – a problem compounded by translations of varying quality and a translation of History of Madness, which while a wonderful literary work, was a rendition of an abridged version of the huge original volume (Foucault, 1965). Writing in 1980, James Clifford voices his exasperation:

‘His well-known stylistic excesses, his confusing redefinitions, abandonments of positions, and transgressions of his own methodological rules may well be aspects of an ironic program designed to frustrate any coherent formulation, and thus ideological confiscation of his writing. Foucault’s work will not occupy any permanent ground […]’ (Clifford 1980: 213).

Another critic, G.S. Rousseau, himself not averse to a spot of literary hyperbole, in one of the more substantial early articles in English on Foucault wants to cover all bases:

‘Poet, Romantic, Blakean heretic, romantic pessimist, imaginative rationalist thriving on the lure of the Platonic “One and the Many”, universalist terrified of the possibility of an empty nominalistic universe, child of Hegel and brother of Nietsche – Foucault is all of these […] Furthermore [he is] Eliotan and modern’ (Rousseau, 1972-3: 250).

But turning more directly to the subject of today’s post – the second radio interview: Foucault clarifies something that has confused many critics of History of Madness. Madness operates at two levels in his work. There is the everyday lived experience of madness in all its bodily, social and historical materiality and then there is its symbolic, poetic and cultural function, emerging in artistic and imaginative works as an indicator of truth (p.18). These are two separate if intertwined experiences. Many critics have accused him of romanticising the sufferings of mad people and wanting to return to the good old pre-scientific days before the advent of the scientific systems of psychiatry and the other psy and medical disciplines. [2] But Foucault is really arguing against the reduction of madness to mere mental illness – saying that it is far more in addition to this. Nonetheless, the critics may have a point. In History of Madness, there is more than a hint of what looks like a nostalgia for the times when madness was crowned sovereign in the imagination of the limits, speaking with the voice of truth about the limited place of humans in time and space and the inevitability of suffering and death.

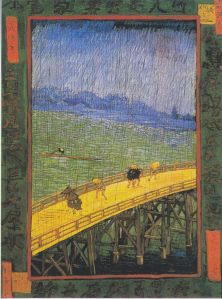

In the second interview in Entretiens Radiophoniques, there is a subtle shift away from this flirtation with an essentialist and universalist link between madness and truth. Foucault argues here that madness is only visionary if a society allows it to be. He specifies that this vision ‘is not a property of the nature of madness; it is simply a series of divisions that are made within a culture’ (p.18). He goes on to argue that in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, literary, artistic and theatrical expressions were given free reign. He traces the muzzling of the visionary force of madness in Western societies and the dousing of the truth it was able to reveal and communicate through culture and art. The ‘tragic experience’ of madness, as he writes in History of Madness (HF: 27-37), reveals the strangeness and disorder of the world – the possibility of the eruption of chaos and human extinction. It is a reminder that the technological systems, reason and order humans seek to impose on existence are not boundless.

Why did madness lose its voice? Foucault argues that the growth of economic mercantilism, the rise of the bourgeoisie and attempts to establish a rational society which saw madness as the direct opposite and negation of reason were major factors (p.18). There is a perception, particularly in the older secondary literature on Foucault, that before 1970 he ignored social and political realities and had nothing to say on these fronts. This view was to some extent encouraged by Foucault himself in some of his later writings. But already, his critique of a society based on the elevation of the importance of money, productivity, work and economic exchange is apparent. In such a society: ‘it is clear that there is no place for people like the mad’ (p. 19).

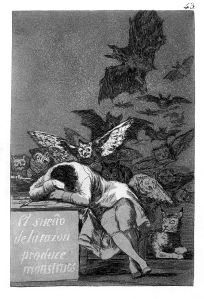

But in spite of the best efforts of these nascent forms of economic rationalism, there was still enough “explosive force” (p. 18) in madness for it to re-emerge and Foucault cites the work of Goya and Sade at the end of the eighteenth century as a demonstration that attempts to silence and ignore the limits and the threat of disorder can never be successful. Again, there is a subtle change with respect to the arguments in History of Madness. In the latter, the work of Sade and Goya is a sign that the silencing of madness was ‘merely an eclipse’ (HF: 27) rather than the dying embers of a once vital incendiary force. They are a prophetic sign of an age to come – one of unbridled dominance over the non-human environment and the dissolution of human community into a solipsistic individualism driven by wants that can never be satisfied.

Foucault expands on the ‘half light’ and ‘twilight’ of Goya’s images of madness in History of Madness (HF: 361) noting: ‘[Goya] renews a connection, beyond memory, with the old worlds of enchantment, of fantastical rides, of witches perched on the branches of dead trees’ (HF: 531). But it is a madness spinning in the void. It is a sign of a new order where man reigns supreme with complete dominance over the physical, social and natural world. Unlike the earlier work of Bosch or Brueghel, these images are not connected to the physical world and our material environment. As Foucault puts it poetically: ‘no star lights up the night of the great human bat-like creatures to be seen in the Way of Flying. What tree supports the branch where the witches cackle?’ – we see ‘no landscape, no walls and no décor’ (HF:531). Madness reveals a new truth: ‘[it] has become the possibility in man of abolishing both man and the world’ (HF: 532).

As for Sade, his work annihilates nature and human community: ‘Sade casts man into a void that dominates nature from afar, in a total absence of proportion or community, in the endlessly recommenced non-existence of satisfaction’ (HF: 533-34). Centuries later, we see the echo of this logic in the endless scroll of social media and isolation into curated individual feeds on individual screens. Foucault continues: ‘this whole society, whose sole bond is the refusal of any bond, appears to be a radical dismissal of nature […] and the free exercise of sovereignty over and against nature’ (HF: 533). By ‘nature’, Foucault means not just the non-human world but the embeddedness and intrinsic belonging of humans to the material world within a network of social existence with other humans.

Madness becomes the revelation of a nihilist violence – a dark mirror of what was to come – revealing the possibility of the destruction of relations both human and non-human and their material support. It becomes a sign of a society which holds up as an ideal an unlimited dominance, dismissal and exploitation of the physical environment in the service of an isolated sovereign individual unconstrained by social and community relations or even by physical materiality. It is the indulgence of desires and ‘freedoms’ to infinity in a featureless virtual void without space or the time of bodies and seasons. Hence the digital nomad, freely drifting from country to country with only a virtual connection to a workplace. As many practising this lifestyle have found – it can become a miserable, lonely and ultimately unproductive existence in the absence of embedded ongoing community ties and rituals (Bratt, 2025).

But as Foucault recognises himself, perhaps he made too close and essential a link in History of Madness between madness and a certain awareness of the truth of our limited human condition, its crumbling into disorder and the possibility of our extinction. He very quickly replaces madness with death as the historical vehicle of this experience in his 1963 books Raymond Roussel and The Birth of the Clinic (See O’Farrell, 1989: 79-84).

If we take Foucault’s idea of a “tragic experience” and loosen its ties with madness and death, where might we see it today? Perhaps we can see it in the cultural production around climate change and environmental degradation – in the awareness of the threat to the equilibrium of Gaia. This is the imaginative and mythological term famously used by scientist James Lovelock to refer to the earth systems and environmental network within which humans are embedded (Lovelock, 2021; See also Latour, 2017). Associated with this is the rapidly increasing threat of the machine – so called generative ‘AI’ and the Large Language Models which turn human communication into a magical machine gushing out words at lightning speed far beyond the speed of human speech and writing, and powered at the material level by the twin exploitation and extraction of environmental resources and human slave labour (Cant et al, 2024; Muldoon, 2024). All this has physical consequences either directly or indirectly for living conditions and generates social, cultural and political instability as people struggle for resources, power and territory in the face of accelerating inequities in distribution.

As Latour and others insistently argue, we may be currently witnessing a new and genuine Copernican shift– a radical decentering of the anthropological perspective (Latour 1992; 2024). The new geological sciences are revelatory of just where humans stand in the immense expanses of geological time and the disproportionately destructive effect of our technologies – to the point where, as some argue, we may extinguish ourselves just as surely as the previous five geological extinctions (Kolbert, 2014). In History of Madness Foucault cites Ronsard writing in 1562:

“Justice and Reason have flown back to Heaven

And in their place, alas, reign brigandage, Hatred, rancour, blood and carnage” (HF:25) [3].

Ronsard was writing in an era that very much believed it was living in the end times. If these phrases resonate today, it is because we are living in an age where the dread of end times is once again upon us.

Notes

[1] The translation of ‘le fou’ poses a certain number of problems in English. In French grammar, ‘le fou’ can be used in a general sense to designate both males and females. It can also be used to designate a male in particular. A separate word ‘la folle’ is used for a mad woman in particular.

[2] For a summary of some of these criticisms see O’Farrell 1989, pp. 78-9.

[3] For background on Ronsard’s Discours des misères de ce temps see https://odysseum.eduscol.education.fr/discours-des-miseres-de-ce-temps-introduction-generale

References

Emily Bratt, ‘My mind was shrieking: “What am I doing?”’ – when the digital nomad dream turns sour, The Guardian, 1 Jul 2025.

Callum Cant, James Muldoon, Mark Graham, Feeding the Machine, The Hidden Human Labor Powering A.I., London: Bloomsbury Press, 2024.

James Clifford, Review of Orientalism by Edward Said, History and Theory, 19, 1980, pp. 204-23.

Michel Foucault, Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason. Trans. Richard Howard, London: Routledge, 1997 [originally published 1967].

Michel Foucault, History of Madness. Ed. Jean Khalfa. Trans. Jonathan Murphy, Jean Khalfa, London and New York: Routledge 2006. [abbreviated as HF].

Frédéric Gros, “Selon Foucault, la folie n’est rien d’autre que l’inquiétude de la raison”, France Culture, Publié le vendredi 21 février 2025. Radio program, podcast.

Eliabeth Kolbert, The Sixth Extinction. An Unnatural History, New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2014.

Bruno Latour, One More Turn after the Social Turn: Easing Science Studies into the Non-Modern World, in Ernan McMullin (editor), The Social Dimensions of Science, Notre Dame, Indiana: Notre Dame University Press, 1992, pp. 272-292.

Bruno Latour, Facing Gaia. Eight Lectures on the New Climatic Regime, trans. Catherine Porter, Cambridge: Polity Press, 2017.

Bruno Latour, If we lose the earth, we lose our souls, trans. Catherine Porter, Sam Ferguson, Cambridge: Polity Press, 2024.

Emmanuel Le Doeuff et Thierry Lesage, À la découverte des thèses annotées de Michel Foucault, Panacée, 28/02/2025.

James Lovelock, We belong to Gaia. London: Penguin Random House, 2021.

James Muldoon (interviewed by Sabrina Provenzani), AI is an extraction machine. But resistance is possible, The Citizens, Sep 17, 2024.

Clare O’Farrell, Foucault: Historian or Philosopher?. London: Macmillan, 1989. Ebook edition 2016.

G.S. Rousseau, Whose Enlightenment? Not Man’s: The case of Michel Foucault, Eighteenth Century Studies, 1972-73, 6, pp. 238-256.

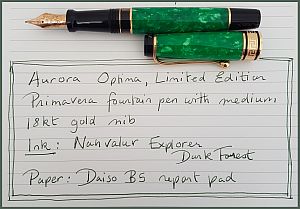

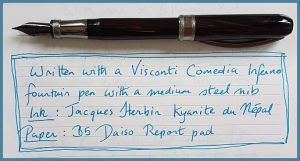

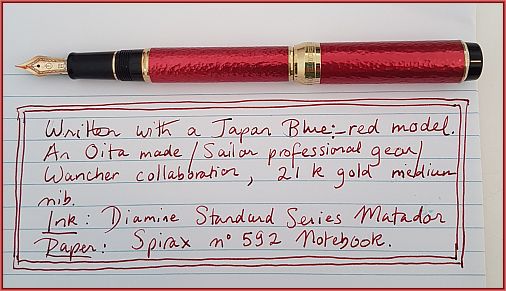

I have used multiple pens, inks and papers to write this post, but will nominate the pen I began writing the post with. It is the same pen and ink as in a previous post – the BENU 2024 Christmas Astrogem and Jacques Herbin 1670 Violet impérial ink with gold shimmer. This photo shows the pen resting on a delightful weight lifting crab pen holder designed by Tanaka Minoru. These plastic crabs come in a variety of colours.